Discover more from Fear of a Microbial Planet

I recently talked with renowned Oxford epidemiologist Dr. Sunetra Gupta about pandemic viruses, how the “immunological landscape” of population immunity affects their spread, how SARS-CoV-2 is not all that unusual, the perverse outcome of intervention, and how she doesn’t lose sleep worrying about an apocalyptic pandemic (transcript edited for clarity and relevance).

ST: I guess I wanted to start with—everyone had their own reaction to when the virus was first reported in Wuhan in 2019 and then as it spread and there started to be a ramping up of news stories—what can you say about your thoughts when you're first hearing about that, and when you got a sense that this was a going to be kind of a monumental event.

SG: Well my thoughts when I first heard there was another coronavirus around was that it would either do what SARS1 had done—either like SARS1 it will not really spread, you will have an epidemic—literally an outbreak—and then it would go away or it would establish itself and become endemic, like the other coronaviruses. And I think that’s the general pattern when new viruses are introduced all the time into the human population and whether or not they are established depends on whether or not they are transmissable.

But the other really important factor is the immunological landscape on which they land. And the immunological landscape for SARS-CoV-2, I thought and continue to believe, will be made up of cross-reactive components, with other coronaviruses, particularly the other beta-coronaviruses. So I think that’s what’s really the big barrier to overcome when things start to emerge.

So I expected that either a hole had opened up, in other words, something like this was circulating long ago and had dropped out of the ecosystem, but then now once again that hole had opened up, just as it did for influenza, the 1918-type influenza, in 2009. I saw it as that kind of an event—I could immediately see the risk profile was very similar to SARS1 in that only the elderly were dying. So I thought if it is going to spread through it will spread through and mostly we won’t notice except for there may be more deaths in the elderly. So I had very similar thoughts about what it would do and what we should be be doing in terms of protecting the elderly—I didn’t immediately figure out that there would be other co-morbities. I thought it would spread through and the death toll would be focused in the elderly.

At the end of December I got quite ill and am pretty sure I had SARS-CoV-2. I had COVID, and it wasn’t too bad. I could function—I didn’t take to bed with it at all—I just had the usual kind of complaints—significant loss of smell, etc. So I was pretty convinced—syndromically there was indications it was spreading through.

ST: When did you realize that it wasn't going to be SARS1, like in that way it's transmitted and the scope that it was going to be, ultimately—

SG: As soon as I saw people getting quite ill with something that looked to me a lot like COVID as it had been described. So by the end of December, and certainly by the time I got it, and a lot of people getting ill at the same time, after there was a lot of illness in January and February—a lot of people were convinced of that, actually.

ST: Obviously things got distorted from Italy and other places about fatality rates. What made you think it was much lower than reported? I suppose you already answered the question because everyone around you seemed to be getting it.

SG: If you just look at the natural dynamics of an infectious disease virus like this it spreads quickly and it was very likely it had already spread if it got to the point in Wuhan it was detectable—like there was a cluster or detectable cluster of cases—to me indicates that the thing had been spreading for awhile.

ST: So you were never confident that this was something they were catching early on, and by the time you find it it's probably too late to to contain it, at least?

SG: Given the air traffic out of Wuhan and into other parts of the world, I think that was the first argument I had with one of my colleagues who was doing the phylogenetics, and he said, “it came out of this market”. And I said, “no, that can’t be true. It doesn’t make any epidemiological sense that it would’ve have already reached the U.K.”

ST: I didn’t intend to get into this too early, but what were you thinking about how long it had been circulating?

SG: I imagined it could have been circulating in the rest of China much earlier, if this cluster started appearing in December it definitely would have been there from October, I imagine.

ST: I’ve heard people talk about sequencing—based on the mutations and doing that sort of phylogenetic study it shows it couldn’t be any earlier than October, or do you think it’s possible it could be earlier?

SG: I think it’s possible that it was earlier, but you know what that means is whatever then came out and spread around the world, the origin that converges to.

ST: So you’re saying you’re gonna have numerous clusters that didn’t make it out—and you’re sequencing the one cluster that made it out.

SG: Having said that, if you think about the logic of it, I guess if it had been highly prevalent earlier in China, it would’ve gotten out. Was it circulating in Taiwan or other places? It’s difficult to do, and all you could do was speculate. It’s much more likely now that it really started to take off around September, October.

ST: John Ioannidis wrote a paper about different IFRs in different places, and if you think about these calculations with different people and different places and with different groups of people it’s something that gets really complicated. It’s the kind of thing that’s difficult to explain to people, so how to you explain nuanced information to the public? Not just about IFRs but also things like herd immunity?

SG: IFR is not that difficult, it’s just that people tend to get confused because they think—the main thing you have about the IFR is that it’s so distributed. I think the IFR—I think Ioannidis calculations are too high. I think for most people the risk is really low, for healthy people. And depending on the metabolic health of the population and how many elderly people there are, the mean will shift. But in terms of the average person’s risk I think it’s very low. The average person’s risk is not the average population risk. People get confused about that. The point is that I think that most of the infections that happened in the first wave went completely unnoticed, even if they were symptomatic they were not classified as COVID, so I think we grossly overestimated the infection fatality rate.

ST: The thing that strikes me about some of those calculations is that you have a different IFR in populations, if you look at Japan, for instance, you know it was very low, and they didn’t do a whole lot to stop it. How to explain places like that?

SG: The Japanese have excellent metabolic health. They have low levels of obesity and diabetes and are overall healthier.

ST: So that was the key, just to have a healthy population, as opposed to what you do?

SG: Exactly. The main correlates of the death toll were what proportion of the population is clinically obese. I expect there to be a correlation but, diabetes, obesity, alcoholism, a lot of things I think were anecdotally and in the data it’s very clear now that they were risk factors.

ST: So, as far as nuanced information, I’ve also mentioned herd immunity, which I don’t know if you know my background but I’m not a population immunologist—instead I use animal models to study infectious disease, you know one gene is knocked out in one animal compared to a nearly genetically identical control. Pretty well-controlled experiments. But I teach the concept of herd immunity in a first-year medical student course and it’s even difficult for me to sort out the nuanced concepts there as well. There’s an article that came out, Anthony Fauci was a co-author, that said the concept of herd immunity does not apply to SARS-CoV-2. Do you think that’s the case?

SG: No, I think that’s absolute nonsense. That is Epi 101. What is herd immunity? Herd immunity is essentially a threshold, a threshold where the proportion immune at which or beyond which the infection rates will start to fall. So if you have equations describing the rate of growth of infections it’s the point at which it becomes negative and it becomes negative when a sufficient number of people are immune. Because that’s the resource for the pathogen.

So it’s like the standard ecological process where once the lions have eaten all the antelope or a certain fraction of the antelope, there won’t be enough to go around for each lion to have more than one baby. There’s a very simple heuristic about once the proportion immune is above that level the infections will drop and once it’s below that level infections will rise. The thing is when infections drop, the number of immune also starts to drop, because that’s no longer being replenished and in the case of SARS people lose immunity, and with every other coronavirus. We knew this, this is not a new feature. So if you lose immunity—what does that mean? That means it does not alter the herd immunity threshold at all. The herd immunity threshold is independent of the rate of the loss of immunity, this is a fundamental result which a lot of epidemiologists, not even, you know at least Fauci is not an epidemiologist. But there were epidemiologists quoted in Nature, saying, “Oh well if you lose immunity quickly, not sure the concept of herd immunity applies.” Complete nonsense! I mean, it’s such fundamental nonsense that it’s shocking these people have jobs as epidemiologists.

We’ve set up a charity called Collateral Global which documents lockdown harms, but we also have an educational part where I put up some explainers up there. I use this sort of cistern analogy, where I said that herd immunity is the level of water that is reached, which is at which point the water stops coming in, and that has to do, not with the rate at which water flows in or out, but with the fundamental characteristics of the system. The water can also flow out quickly or flow in quickly, that’s what SARS is like, whereas measles flows slowly because you have lifelong immunity and it trickles back in when susceptible children are born.

ST: Then you also have two types of immunity, sterilizing and non-sterilizing that just protections from dying and obviously that’s what’s very different here is the fact that when we have different waves, sterilizing immunity goes away and antibodies go away, does that explain why we have waves?

SG: Yes, so that is a very fundamental feature of coronaviruses. The rate of the loss of immunity doesn’t matter, you just get waves, and the interval between the waves is all that is really affected by the rate of the loss of immunity. But what that means is that herd immunity is maintained by reinfection. In measles, herd immunity is not maintained through reinfection, it’s maintained through the maintenance of sterilizing immunity, whereas in other diseases like coronavirus infection herd immunity is maintained through reinfection and you made the crucial point that reinfection does not carry with it the same risks of of severe disease and death, that all of that risk is taken care of or focused on the first infection. So the first infection gives you lifelong protection against severe disease and death.

For me this is easy to separate (protection from infection vs. severe disease and death) because I’ve worked with malaria, where it is very obvious that your first infection can land you with a very severe case and that’s what kills the babies is severe malaria. And upon their first exposure, that’s what kills tourists, the first exposure is very dangerous. But in malaria, you keep getting infected every season if you live in a hyper-endemic area, and then subsequently you get what’s called mild malaria and eventually stop getting mild malaria but are still available for infection and then after like 15 years of living in a hyper-endemic area you get some incomplete protection against infection. So those three things separate out very neatly in malaria.

It’s also true of these viruses like coronavirus, and probably RSV, all range of respiratory viruses, and fundamentally it’s true of flu, if you think of flu as one thing.

ST: Do you think viruses have a certain biology, or maybe a certain immune response to those viruses, such as coronaviruses compared to measles, which spreads differently. What is the biology of the virus that controls what it’s doing (in terms of sterilizing antibodies)?

SG: Certainly, if I’m comparing measles and flu is that with measles, one of the major neutralizing antibody epitopes (i.e. the part of an antigen recognized by the immune system) is located within the receptor binding site, and it really cannot change so if the conserved epitope is highly visible and elicits strong durable memory responses then those are the sorts of disease that sort of fall into the common childhood infections where you get lifelong immunity. And, not surprisingly, those are the diseases against which you can make vaccines easily, because we just need to mimic natural immunity to make a sterilizing vaccine.

Now the question is why don’t antibodies to the spike protein do the same job when it comes to flu we can say because of antigenic variation, the next strain of flu there’s immune immune evasion, and with SARS-CoV-2 we’ve seen antigenic variation and some immune escape as well. But, if you just look at all the other coronaviruses, it isn’t just that they vary antigenically. If you look at malaria, it’s also true that some antibodies against conserved areas are just ineffective. It might have something to so with the quality of CD4 help, or that the epitopes are cryptic, like the stalk region in flu, you can make antibodies to it, but they aren’t going to be protective. Also to an what extent is it not just the antibody response, but the accompanying mucosal immunity, T cells, etc.

ST: Calculating IFR and estimating herd immunity involves a lot of uncertainty. I’m not a psychologist but I’m really interested in the psychology of of how people behave, and I feel like the public really demanded, at least from scientists and leaders and health officials, that they believed the public demanded certainty, even when they couldn’t give it to them. How do scientists communicate uncertainty? I felt like the leaders did a terrible job of this and I think they offered certainty when they couldn’t. What are your thoughts on that?

SG: I just gave this talk on Wednesday about four problems we have specifically with the mathematical modeling aspect of it but it’s probably quite general—the first of which is this sort of illusion of certainty, and actually Jeffrey (Tucker) really likes this essay that I wrote 20 years ago that he keeps coming back to. But I was already worried 20 years ago about how mathematical models, to the general public, they really look scary and hieroglyphic and have the pertinence of truth, and there’s just something about them that needs to not be exploited. So mathematical modelers must be careful, whatever discipline, to not convey that sense of certainty that arises from how difficult and impenetrable and scary these things are. Because, in fact, none of the predictions—they were just hypotheses—they weren’t the truth. There’s no such thing as “The Science”—that’s a contradiction in terms—yet that was the political plan. “We’re going to say that there is “The Science” and we’re going to say that this is what you have to do” and the people will do it. What’s remarkable to me is that the scientists played along with it.

ST: I think there's almost like a natural selection of the scariest model, so you have thousands of models out there, and who are the media going to pick? Obviously, someone who's well funded and has lots of media visibility already. But they also gravitate toward the scariest model, I mean that's the one that gets attention. And if you are the scientists that developed the model, you are under pressure to not to fight back against that, because you’ll get more attention. I thought there was a real selection pressure there that had had a quite an effect on what what was shown and maybe the reason why leaders embraced lockdowns and mitigation policies that were over the top, that sort of spread around the world like a virus. What do you think happened there?

SG: I think they just panicked, because all the various health systems were likely to buckle and that’s because they are underfunded and have no resilience, not because this is necessarily an exceptional pandemic. So they got worried they would be blamed for not protecting the citizens, and they got it into their heads that lockdowns would stop the spread and they decided that was obvious.

ST: Just from China? What they were doing was mimicking China?

SG: I didn’t see, certainly in my experience, certainly of the Western world I have never seen an appetite to imitate China so I don’t think there was some sort of conspiracy by the CCP forcing this on us. Lockdowns are very much a part of history of the Western history as well, they just haven’t been used. But the truth is that the “why” of lockdown mutates and that mutated even during the course of the pandemic.

The first reason you lockdown is there’s sort of an altruistic lockdown, which is where you are locked down so the thing doesn’t get out. And even the first Italian Bergamo lockdown was in some part, if I remember correctly, done for that purpose. Kind of “Oh shit, it’s gotten to Bergamo and we can’t let it out into the rest of Italy or Europe”. So that’s more of an altruistic lockdown.

Then, of course, there’s the lockdown to keep it out, which is what New Zealand and Australia, the remote islands, indulged in. That’s clearly not altruistic. However, if we had an coordinated international effort to stop it from getting to places that it already reached, it may not have been an unreasonable thing to do for a period, until people had figured out a better strategy. But what happened, instead, is that these island nations started gloating about that policy. And they held themselves to somehow have done something that was superior and indulged in the most egregious form of virtue signaling seen in a long time. There’s a certain logic to that, at least.

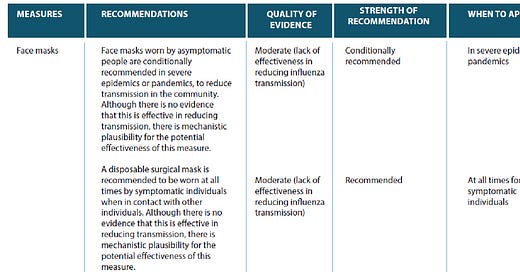

But it’s very much harder to keep a virus, once it’s entered, to stop it from spreading. We know that everyone being isolated from everyone else that it can stop the spread and we know that if everyone mingles as they do there will be spread, but in between those two extremes it’s not just a linear growth, what’s very likely as soon as abandon this “gaffer tape” lockdown, that’s it, it will spread. And you might not really be able to slow it much at all and that’s what we’ve now seen. And then, of course, come the weird performative things like masks and social distancing and all that, which I almost think it’s obvious those things wouldn’t work.

ST: There’s been some reports about viruses behaving differently, when lockdowns are lifted. We had giant RSV spikes in the summer in children and it’s not something we normally see. Physicians in the west coast I’m hearing are seeing a lot of influenza, and this isn’t normal (this time of year). What do you think about that as being a sign that lockdowns work sort of but then once you lift them, not only do you get SARS-CoV-2, you get everything else?

SG: Yeah, it’s even simpler than that. Lockdowns don’t work against epidemic diseases and they work to transiently suppress endemic diseases. So if you think of the herd immunity threshold as something around which endemic diseases is bobbing up and that heuristic being that once the population immunity dips below the herd immunity threshold you’ll get an outbreak. That balances it up, it overshoots typically, so then it will start to come back down and you get the same thing. And that’s how these diseases operate—suddenly, what a lockdown is doing is lowering the herd immunity threshold. For the endemic disease, they will nosedive, because since so much of the population is already immune, as soon as you lower the herd immunity threshold, those will be transiently locked out. But for epidemic diseases, that’s not the case so dropping the herd immunity threshold a little bit, which is what lockdowns did, so in that regard you’re absolutely right, it’s not like they had no effect. But it was the least desirable of effects which is that the endemic diseases got knocked out for a bit, then they come back in full force.

Because it’s been delayed, you see something that we teach a lot, which is that we call the “perverse outcome of intervention”, which is that interventions increase the average age which someone gets the disease and if severity increases with age, then you might get a kid getting adeno(virus) and they’re having a liver transplant rather than a mild, blocked nose.

ST: Do you think that has anything to do with this mysterious hepatitis--(outbreak in children)?

SG: Yes, I think what’s happening—it’s a hypothesis—is you’ve got it coming back to a lot of susceptible kids who haven’t had it yet are all getting it at the same time. So any rare severe outcomes will suddenly become a lot more visible.

ST: With adenoviruses specifically?

SG: Yeah. And the other thing is that if there’s, as with many diseases, certainly hepatitis A, for example, chicken pox—severity increases with age. The age of first infection or age of infection is a big determinant. Look at EBV, I mean there’s so many—polio—it’s a commonly observed phenomenon that if you intervene you raise the age of infection and you get a perverse outcome, not just in terms of disease outcome itself, but often in the congenital syndromes—so rubella you push the average age up to childbearing age when you get a congenital rubella syndrome. You want to get rubella when you’re a baby and certainly before you get pregnant.

ST: I could talk about that for a very long time. That’s a very interesting topic and something I’m thinking about for my book a lot. But (in the interest of time) I’d rather get to this meaty stuff, like how you’ve written about how globalization might actually provide protection from future pandemics, as the ability to share viruses throughout the world’s only limited by the length of a plane ride, so I want to discuss that a little bit, because I think that’s a very interesting concept.

SG: I prefer to call it “international travel” because I think “globalization” has a very particular kind of economic connotation..But yeah, increased early exposure to related pathogens I think gives you protection against these pandemics. It’s possible the reason why many of us didn’t have very bad outcomes at all from this virus is because we’ve all been infected several times over with other beta-coronaviruses, and you know, many labs, including our own, have shown that there’s quite a lot of cross-reactivity between the S2 part of the spike, not to mention the T cells.

ST: Do you think it’s possible to show that some of these populations that did well have specific types of cross-immunity that protected them better than other populations? Ist that something that’s going to be, at that scale, doable (experimentally)?

SG: Certainly, that is a hypothesis. That Japan, for example, may have had a very recent—maybe a recent exposure to a beta-coronavirus like OC43 could well have protective effects.

ST: Is that something that we could do by serology?

SG: Well that’s exactly the first thing we did—we put out there a paper showing on the basis of the data in March 2020 you could not tell whether the pandemic had already basically swept through or the first wave had occurred already and what we are seeing now is just the residuals or whether it’s only just come in and a lot of people are going to die, which is what the Ferguson models were predicting. And so what we said was not, “oh, we think the pandemic is over”. What we were trying to say is “we don’t know the extent to which it spread, let’s go and find out. We can’t say anything about what’s going to happen. The only way we can figure this out is by testing it.”

So, in fact, in my lab we developed by the end of March 2020 we had neutralizing psuedo-neutralization tests. So we got some blood donors from Scotland and the detectable neutralization antibody levels were around between 5 and 10% in Scotland.

But I think there was already a reluctance to perform these studies—there was a huge backlash—nobody would give us the data. And, of course, what I didn’t figure is that the antibodies would decay very quickly if they were made at all. So actually it wasn’t the most useful test.

ST: The last question I want to ask is—so Hollywood likes to depict a doomsday pandemic that kills nine out of ten people in the world—or even more—do you think that with international travel (and cross-immunity) that’s even possible? Why or why not?

SG: Well, Ebola was pretty bad in terms of it’s case fatality rate. But when something has that kind of case fatality rate you do detect it quite early on and generally speaking, also means that it could be harder to spread. The worst combination is something that has a long incubation period and then inevitably kills you but which I suppose in some ways was what HIV was, with a very long incubation period. And that’s why it was so terrifying, except of course, it wasn’t as transmissible because it is sexually transmitted—there were ways that one could think about controlling risk.

I think it’s unlikely we will have the novel evolution of a bug that is highly lethal, has a huge IFR and also is not detectable until it’s really spread. But certainly under those circumstances we will have to think of some ways of isolating people.

ST: It would have to have those characteristics? Long incubation, highly transmissable?

SG: Yeah, because otherwise, if it just has a high IFR, you’ll see it, which is what happened with Ebola.

ST: I know someone who was sent to Africa, what he said was they just educate basic germ theory, and that’s enough.

SG: I just say don’t touch someone, a dead person.

SG: Yeah, I don’t think it’s something I would be losing sleep over.

Thanks to Sunetra for answering my questions and offering another interview, since we ran out of time before we could discuss the (probably too many) topics I had outlined. An amazing resource for any aspiring germophobia therapist!

Brilliant-both of you. Thank you!

Wow great column and what a coup to hear anything Dr. Gupta tells us. And you're right, there are many other points that I would love to see you write about - ADE, OAS, the persistence of performative/ineffective NPIs that continue after many mandates have been lifted etc. There's also the phenomenon of media capture, mostly in urban markets (blue states), that is then embraced by those readers. You wrote about this several months ago. Not sure there's anything to do about it, other than let our votes do the talking in November.