Discover more from Fear of a Microbial Planet

A Human Need For Community

Trading human connection for the appearance of safety is a tragic mistake.

On March 11, 2020, a local TV reporter called the campus office and asked if anyone was available to comment on the newly recommended practice of social distancing to prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2. I didn’t really want to do the interview. But, I could tell my center director was in favor of it, so I agreed. I had already talked with a local newspaper reporter, and had tried to allay the fears of local residents with calm and careful language. I could see the public’s mood was approaching panic levels quickly, and I felt the potential damage that mass panic could do was even worse than the damage from SARS-CoV-2.

The reporter arrived later that afternoon, just him and a camera. He told me that his goal was to reassure the public, and give them some information about precautions they might take. That reassured me, too. We did the interview in my office, and he asked me some basic questions about social distancing, hand washing, etc. He asked me if the media was to blame about the growing panic in the country over COVID-19. I told him that there were still a lot of unknowns, and the situation was definitely concerning, yet the worst-case scenarios were getting the most emphasis in the press, to the point that they were perceived as the most likely outcomes. I said that the number of reported cases was likely much lower compared to the true number of infections, due to the bias of reporting only severe, hospital-related cases, and the ignorance of the number of mild or asymptomatic infections. I said that although more people may be spreading the virus, infections were likely to be more common and less lethal than reported.

Then he asked me if there was anything else I thought people should know, and I told him that although it was important to be cautious, people shouldn’t be afraid to help one another, especially as a part of churches and civic organizations. My fear was that the fear of viral spread would become so great, that these community groups would cease to operate at a time the community would need them most.

Unfortunately, that part didn’t make the cut on the news that night, because it was the most important thing that I had said.

Outsiders in the Tower

On October 5th, 2021, longtime NIH Director Francis Collins announced he was retiring from his position at the end of the year, a position he has held since 2009.

There are many reasons why Dr. Collins is a remarkable individual, and not the least of them is that he is a practicing Christian.

This revelation wasn’t well-received by some of his peers. Many scientists think religion is an outdated stain from our primitive past, and yet remains the root of many of our current troubles. To many academics, religion is akin to superstitious thinking that is best left behind in favor of things that can be observed, measured, and tested. Scientists in positions of power should not engage in such antiscience behavior, they might say, when science is the the only true way to acquire knowledge. This typifies Scientism, which is a religion in its own right. But that’s a whole different post.

I have spent much of the last two years questioning the rationale and wisdom of the pandemic response, and it hasn’t made me very popular in some circles. Yet being an outsider isn’t exactly a new experience. I work in academia, and although I share this space with many friends and people I like and admire, I’ve never fit perfectly in this world. I grew up in the Midwest in a middle class neighborhood (maybe lower middle by today’s standards), and neither of my parents are college graduates. I was raised in a religious family, and went to Lutheran schools until college. To many of my colleagues, I might as well be from a foreign country.

Like most people, I rebelled against my upbringing when I went away to college. The area where I grew up in Northwest St. Louis County started to seem small, insulated, and decaying compared to the rest of the world. My professors seemed to be worldly with a big view of everything, and I wanted to have that, too. The process of science seemed to have unlimited potential for solving every problem of the world. Many of my fellow college students were eager, energetic, and unapologetic about their academic interests and ambitions. It was as if I had stepped out of the dark ages and into the enlightenment by just moving a couple hundred miles. I could never go back, and that was fine with me.

After going through college, working as a technician at a large medical school, graduate school, and a post-doc, I could start to see the cracks in the view that the scientific community was all I needed to live a satisfying life. Although I had met and befriended some great people much different than me, I could see some the scientific institutions I had joined were less than perfect. Scientists could be brilliant and engaging, but also petty, arrogant, biased, and completely detached from the experience of the average citizen, even as they claimed their work was critical for helping the public. Government and academic institutions often veered very far from their stated missions due to the very human pursuits of security, power, and influence.

All of this was understandable, because I knew that humans are fallible, and always will be. But what seemed obvious to me also seemed harder for non-religious people to accept. I started to realize that maybe I hadn’t left my beliefs behind.

After I met my wife and settled down and started to discuss having a family, I started to think more carefully about my religious upbringing, and felt that many of the positive characteristics I saw in myself might’ve been enhanced by my experience.

There are areas of science that agree with this. My wife, who was studying public health, pointed out that children brought up with religion in their lives are less likely to get involved with drugs or engage in promiscuous sex or criminal activity. Being raised in a community of people with shared beliefs has tangible benefits, even beyond the critical need for humans to discover a deeper meaning beyond the physical, observable universe.

When we moved to Indiana, we joined a church near the university, and were happy there. There were many members there who were doctors, lawyers, or professors like us. And there were lots of children. It seemed to be a perfect bridge between two parts of our lives. Many of those church members felt like outsiders in their academic worlds, too.

A Virtual Community is Not a Real Community

The Sunday before the TV interview, the pastor of the church was ill and couldn’t make the service (this was never proven to be COVID), so the members had to improvise. Even though there were no confirmed cases in town, I was already very worried about mass panic, and I thought people might read too much into the pastor being sick, so I volunteered to address the congregation. I told them many of the things that I would tell the reporter in the interview the next week. Most importantly, I told them, was that we could not allow ourselves to fear each other to the point that we hurt ourselves and our families, and couldn’t help our neighbors. I then promised that I would fight anything that prevented us from acting as a real community.

What I didn’t realize is that keeping that promise would make me an outsider in my own church.

A couple of weeks later, everything had shut down, including church services. The elders met online to discuss the future of in-person services. I could tell many of them were terrified. Like most people they had been watching cases and deaths rapidly increase, especially in New York City, and non-stop apocalyptic media coverage. Their new state of isolation had made them even more fearful and anxious. Even without the panic-promoting sensationalism of the mass media, this was obviously a natural disaster that was going to spread around the world. In our discussion, it was also obvious that most wanted to have as much control over the situation as they could have, because they felt responsible for every member. So they decided to go completely to virtual activities.

This was a very difficult situation to navigate. I wanted to give people hope despite the severity of the situation, but also wanted to convey the message that they didn’t really have the long-term control that media outlets and government agencies were promising. Shutting down everything couldn’t last indefinitely, and people couldn’t avoid being in personal proximity indefinitely without serious consequences. The virus was going to spread no matter what we did. With too much separation and fear of one another, we would cease to function as a community and couldn’t help others.

This was not a popular message. Over the following weeks I kept speaking about the illusion of control I felt many were experiencing, but it was largely dismissed. I said that people should be able to make decisions about their own risk, since not everyone had the same risk. Most of the elders disagreed.

In April, a couple that lived on a farm offered to have Easter services on their property. I thought that was a great idea, since outdoor transmission was much less likely. Most of the elders disagreed. It’s just too early, one said. We can’t keep children away from each other or elderly people, an older woman said. That’s right, I said, but we can let people decide for themselves if they want to take those risks, especially if they aren’t what some believe. I said we should treat everyone, including elderly people, as adults capable of making these decisions. They disagreed.

Weeks later, after a large spike in cases did not appear in our region, we began to discuss if, when, and how to restart in-person services. Many elders were still quite fearful about the prospect of gathering again. One said that she thought it wasn’t a good idea to meet “while there is still a possibility of contagion”. I asked them to consider what that meant, and how they would really know when things got better. “Think about what ‘things getting better’ will look like,” I suggested. I could tell that there was little thought into what the ideal environment would be for returning to normal. They just knew that it was going to be in the future. Not then.

A committee was formed to determine how returning to in-person services would be accomplished “safely”. I wasn’t asked to be on the committee, but my wife (who was months from finishing her Ph.D in a public health field) and I sent them a document suggesting measures that we thought would make people feel safer, while being clear we couldn’t guarantee anyone’s safety. We also didn’t want to destroy the essence of a traditional service, because we thought that would be even more important in a time of fear, anxiety, and great uncertainty.

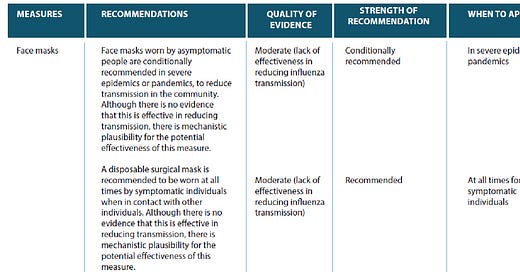

Our document was ignored. Instead, the service the committee outlined didn’t resemble much of a service at all. Tape would be strung within the pews, forcing social distancing. Masks would be required. Elderly members would be discouraged from attending. No group singing or responsive speaking was allowed. There would be no traditional offering and communion would be highly altered. There would be no fellowship allowed after the service. No Sunday school or children’s church. No nursery for babies and toddlers.

I told the elders that rather than transmission, the main thing prevented by the new measures would be group worship. Disease transmission might not happen at the church as frequently, but it still could happen. People just had to accept that. To many this sounded completely unhinged. They didn’t think I was taking the pandemic seriously at all. “Lives are on the line,” one member, another professor, told me. That was true, and not just physical lives, I thought. I asked the question, “Is there ever a case where we would find something more important than our own physical safety?”

Normally, the answer would’ve been yes. A relevant discussion had come up a year before, when there was an active shooter in a church in Texas that had been shot by an armed church member. Arguably, in that situation, the armed church member had saved lives. “That’s just not what we are about!” one fellow member exclaimed during the discussion. “We want to be welcoming.” So in that case, there was definitely an ideal more important than physical safety. I agreed.

But few agreed with my objection to the stripped down shell of a service. One echoed much of what the regional church leadership had discussed during a monthly meeting she had attended online. Based on my understanding of her comments, the regional leadership was even more panicked, and was discouraging congregations from consideration of returning, even to restricted services.

Later, I found out that the regional leadership was under the advisement of one of their own, a former medical technologist (i.e. clinical lab technician) who had styled herself a medical and COVID expert. I obtained a YouTube video of an interview between her and another regional representative, and was shocked at the sensationalized speculation and outright falsehoods this woman was saying with great authority and a with a complete lack of nuance. She talked about the certainty of increased risk of variants, which was completely unknown at that time. She gave misleading numbers about reproductive rates, immunity to variants, and current rates of infection, claiming every country in the world was experiencing spikes in infection. She was incredibly misleading about risks to children, citing a paper that only examined hospitalized children and then applied the results to the general population. Over a weekend, I documented all of the falsehoods and misrepresentations from that one interview and sent it to the elders, the pastor, and a regional leader. It was seven pages long.

Yet, as far as I know, no one else questioned her accuracy or authority. I suspected it was because she was saying what they already believed. She was saying what they wanted to hear.

As the the pandemic continued, it became clear to everyone that an enormous pressure was being put on working families and single mothers. We discussed the possibility of providing some childcare at the church. “If we don’t help people now, when do we help?” one professor asked. I agreed. Then the discussion turned to liability, and the idea was immediately scrapped.

In the fall, the school district implemented an ill-advised hybrid system, which put again put a huge burden on working families. This time, another church in town stepped up, providing a childcare for children on their off days. They were somehow able to get past the seemingly insurmountable obstacle of liability, and many families were grateful and accepted their services. They might have even gained a few members.

In November of 2020, there was a major surge of COVID in our area, and in-person services stopped once again for the rest of the winter. By then, our family had begun to attend other churches. My wife had met a pastor at a local coffee shop, and she told him of our frustration. He invited us to his church in a nearby town, and we decided to attend one Sunday.

The difference between his church and ours was stark. Everything and everyone, seemed normal. No one acted afraid of us. People shook our hands. There were very few masks. We were amazed. If their theology had been a little closer to what we were comfortable with, we would still be going there. But it was an experience that we needed.

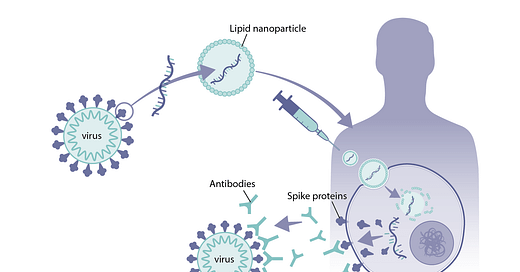

In December, vaccines became available for the elderly. By the Spring of 2021, every adult had a chance to be vaccinated. Another committee was formed to discuss starting in person services again. This time I was asked to attend.

The governor of Indiana had declared that the state mask indoor mandate was ending, conveniently after the Final Four tournament in Indianapolis. One member of the committee mentioned how important it was to evaluate “the data” about mitigation strategies. It was clear that the general consensus was that in person services would start, but with the same restrictions as before. I asked, “if everyone’s had a chance to be vaccinated, then why can’t we go back to a normal service?” I had explained previously why masks were heavily politicized, and the data hadn’t really surpassed pre-pandemic skepticism about their utility. Of course, this went against the CDC’s recommendations, so it wasn’t taken seriously. I also pointed out that mask mandates had been ended in other states, with no consistent evidence of case increases.

It quickly became clear that, in the discussion, we actually weren’t “evaluating the data”, but rather, people’s feelings. It was simply too hard to let go of the sense of security that masking provided. So they would continue to be required. I strongly objected to this, because I thought vaccinated people should act normally, and acting otherwise encouraged vaccine hesitancy, and signaled no real end to restrictions. The others disagreed. At that point, I said that my family, with two vaccinated adults and two low-risk children, were going to come to the service without masks, and act normally, no matter what the rules were.

A week after a pleasant outdoor Easter service (one year late), we did just that. Most people were very nice to us, and I got the sense that some went out of their way to be nice, quietly supporting what we were trying to do.

But there was an obvious tension. We got some hostile stares, and others wouldn’t acknowledge our presence. One family got up to move away from us, as if we were a threat to them. After more than a year of the pandemic, this is how people had been conditioned to treat one another, even in their community. I sent my 5-year old daughter to children’s church, and she was sent back, because she wasn’t wearing a mask.

This continued for a few weeks. It was clear the elders, a group I was no longer a part of, had been discussing our intransigence. Each week, something new happened. First, there was an announcement that being a member of the church came with the acknowledgement of the elders’ authority. The next week, there were signs on the door that said, “Because we love one another, we ask that people wear masks at all times in the building”. In other words, masks were a symbol of love. Members were stationed at each entrance to stop people who weren’t wearing masks. We walked past them without a word.

Finally, the pastor emailed me to let me know he wanted to deliver a letter from the elders. There wasn’t many possibilities about what message that letter could have contained, other than asking us to leave the church. So, ultimately, we did, without ever receiving it. Although we had realized months before, to our sadness, that prominent members in our community really didn’t share our core values, we made one last effort to make them prove it. And they obliged.

My experience is by no means unique. I have met many others (ironically online) who became outcasts in their own community because they tried to stop panic and overreaction to the pandemic that would ultimately hurt everyone. Most failed, and were forced to endure a bizarro world where avoiding human contact became a sign of sacrifice, even in extreme circumstances, like missing the last moments of a dying loved one. This was particularly evident in what has been called The Zoom Class, those able to work from home, many believing they were part of a noble effort. The working class, when they could keep their jobs, went on as before. They had no choice.

The situation is definitely improving in my area. Many places in Indiana are back to normal, except for those more susceptible to political influences, like public schools, universities, and government buildings. We have had some success finding new communities that share our core values, both inside and outside of our spiritual life. This is happening despite continued dire warnings of new variants and promises of new restrictions imposed without any consideration of costs and benefits.

People will continue to seek human connection and communities that share their values and offer physical and spiritual support, because that is a human need that cannot be suppressed without severe consequences. And SARS-CoV-2 will continue to do what it does, spreading and mutating and infecting people, as many other respiratory viruses have always done. It won’t be easy for many to accept this reality, but it is the most important step for people to get back to being human again.

Subscribe to Fear of a Microbial Planet

Fighting back against a germophobic safety culture.

Thank you for sharing this story, Steve. I really believe there needs to be a book written on this specific subject of the failure and betrayal of church leaders to properly fulfil their duty to obey biblical commands to gather, serve, and care for their flocks during Covid.

Great piece, Steve. I think this is very challenging for a communitarian/humanist like yourself to deal with a low empathy community that you had previously thought was not. The transition to larger amounts of emotional differentiation from ostensible peers is very difficult. Utterly predictable from the memetics. See: https://empathy.guru/2021/08/22/elite-risk-minimization-and-covid-empathy-in-the-time-of-coronavirus-ix/