Cholera, 1912 (Free SVG)

The following is adapted from Chapter 4 of my book Fear of a Microbial Planet: How a Germophobic Safety Culture Makes Us Less Safe.

When cholera broke out in London in the first half of the nineteenth century, experts were quick to place the blame on miasma—the accumulation of toxic gases and odors within the atmosphere they claimed was responsible for a host of human misery.

In hindsight, it’s rather easy to explain their ignorance, as London in the early nineteenth century was a foul, fetid place that had exploded in population, yet had retained the lack of sanitation of earlier medieval times. Huge, crowded slums provided the perfect culture media for human infectious diseases. Urine and feces from chamber pots were unceremoniously dumped into alleys or leaky cesspits—there were no sewers of any kind. Trash was strewn everywhere, attracting disease-carrying rats and other vermin. The streets were also strewn with horse and animal manure. Flies were everywhere. Food was judged by how bad it smelled after it was cooked. If you could stand it, it was OK to eat it. Drinking water was frequently contaminated with human waste. There was simply no way to avoid it.

The diary of Samuel Pepys, an intellectual, government administrator, and president of the Royal Society of London, one of the first organizations to discuss and publish the results of scientific studies, provides an unsanitized (pun-intended) picture of the filthy world of London in the seventeenth century. What his diary did not contain was evidence that he ever took a bath, as suggested by frequent complaining of body lice and descriptions of the accumulation of other filth on his body. Instead, his candid accounts detailed spilled chamber pots, eating fish with worms and awakening in the night with food poisoning, culminating in an unsuccessful mad dash to find a chamber pot, whereupon he “was forced…to rise and shit in the Chimny twice; and so to bed was very well again.”

Cellars between neighbors were often shared and could result in seepage and flow of sewage between houses. When Pepys went down to his cellar one morning, he recalled, “I put my foot into a great heap of turds, by which I find that Mr. Turner’s house of office is full and comes into my cellar, which doth trouble me.” I suspect anyone would say that a cellar filled with a neighbor’s feces had doth troubled them, too.

All this unhygienic living, even among the privileged classes, provided the perfect environment for epidemics of diseases like cholera. Cholera is caused by the comma-shaped bacteria Vibrio cholerae, and is transmitted by the fecal-oral route. Individuals infected with V. cholerae develop diarrhea a couple of days after ingesting the bacteria, and in some individuals, diarrhea is severe enough to cause rapid death through loss of up to one liter of fluid per hour. Cholera patients with severe diarrhea lose fluid so quickly that rudimentary treatment beds often contained a hole with a bucket underneath to contain the colonic deluge. Worse yet, choleric diarrhea is characteristically described as “rice water”, and although it may have a fishy odor, the bacteria contained within may contaminate nearby water sources or surfaces resulting in no appreciable odor or taste. As a result of massive dehydration, cholera patients with severe disease experienced severe muscle cramps, irregular heartbeat, lethargy, and a severe drop in blood pressure, resulting in death in one-third to one-half of cases, often within a single day.

Treatment of cholera nowadays is pretty simple, requiring antibiotics and intravenous electrolyte-balanced fluids until the patient stabilizes and the infection clears. But doctors in premodern London had no clue what they were dealing with. They didn’t know about dehydration, fecal-oral transmission, or even the germ theory of infectious disease. As a result, their prescribed treatments often made things worse. Bleeding was still a favorite, where doctors attempted to remove “bad humors” from already dehydrated patients. Also popular humoral strategies were frequent pressurized water-enemas and treatment with emetics that induced vomiting, both enormously unhelpful for already weakened patients. One popular elixir called calomel contained toxic mercury that destroyed patients’ gums and intestines before killing them. Others contained alcohol or opium, which at least provided some comfort patients dying from cholera or other ill-conceived treatments. Some doctors did try giving patients water, but they often vomited it back up. Treatment from doctors for cholera, just as for many diseases at the time, didn’t provide much benefit.

In order to stop the ravages of repeated cholera epidemics, people had to understand how the disease was transmitted. Although the idea of removing foul odors from the atmosphere was an attractive idea in premodern times, in practice it was a complete failure. In the London outbreak of 1832, one enterprising surgeon named Thomas Calley hatched a plan to purify the city’s putrid atmosphere by firing off cannons filled with large amounts of gunpowder at strategic sites throughout the city.

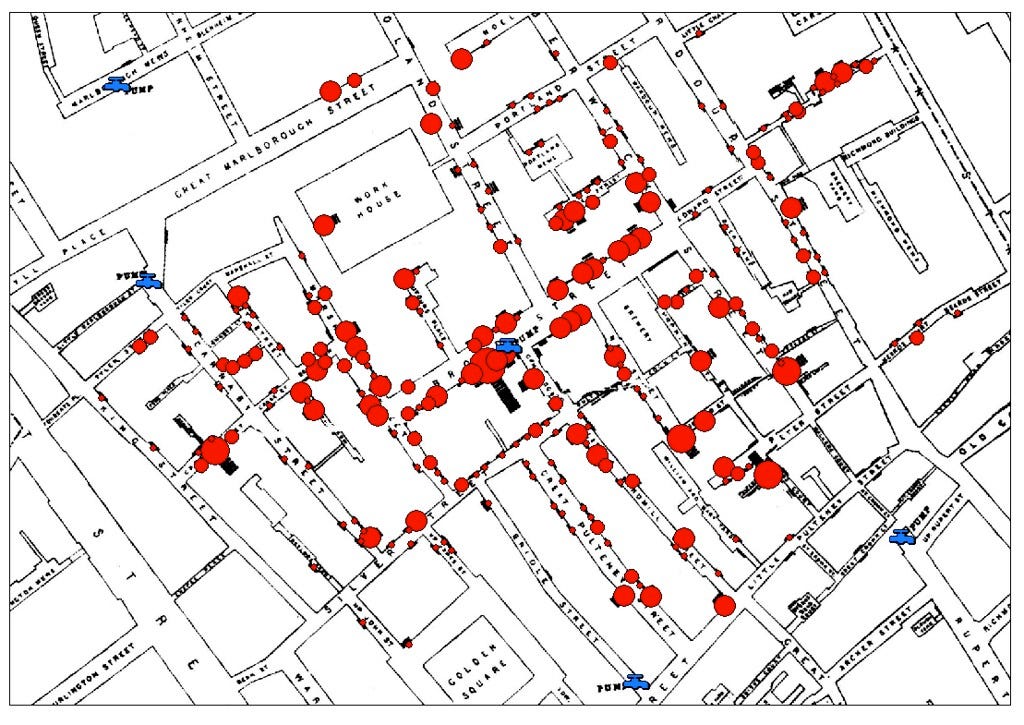

Obviously, that strategy didn’t work, and cholera continued to periodically sweep through Europe unchallenged up until 1854, when the father of modern epidemiology, anesthetist John Snow, reported that cholera was transmitted through water from a contaminated well during the latest outbreak. As author Sandra Hempel detailed in The Medical Detective: John Snow, Cholera, and the Mystery of the Broad Street Pump, Snow had spent the summer going house to house in the epicenter of the recent epidemic, south London, asking where the residents went for their drinking water. Initially, the results were confusing, as some individuals gave conflicting information based on their incomplete recollections of their habits, but Snow developed a test that could distinguish water sources based on their salinity, allowing him to identify sources when residents were not helpful.

John Snow’s map (Jim Surkamp)

In two instances, Snow was puzzled by the lack of cases connected to a prison workhouse and a brewery, both located in the center of the hot zone, and he was able to solve these mysteries by proving that those places were supplied water from outside the area. In addition, the brewery workers were allotted regular draughts of beer, and never drank the water (ie, beer might have saved their lives). Ultimately, Snow determined that a single well was directly connected to the vast majority of cases, a well that supplied the Broad Street pump. He was able to convince the neighborhood authorities to remove the handle of the pump, even though they couldn’t believe it had anything to do with the outbreak.

In fact, Snow’s report did very little to convince anyone. The local “experts” would only accept an explanation rooted in the widely accepted miasma theory. Worse yet, the outbreak of cholera was already waning when the handle was removed from the Broad Street pump, confirming expert belief that it had no effect. Competing investigations had found no such connection, although they were mostly operating under the assumption that cholera was acquired through the lungs by breathing of noxious gases in the atmosphere.

As a result of this belief, the Committee for Scientific Inquiry, led by politician and aristocrat Sir Benjamin Hall, completely dismissed Snow’s ideas. Another member, microscopist Arthur Hill Hassall, had spent much of his microscope time cataloguing the many spurious food additives present in nineteenth century British food products, infuriating legions of shopkeepers that had for years gotten away with, among a host of other transgressions, adding alum to flour, sawdust and rust to cayenne pepper, sulfuric acid to vinegar, and clay to tea. Although Hassall was an expert in food microscopy and chemistry, he rejected the idea of microbes playing a role in human biology and disease, “Many of the public believe that everything we eat and drink teams with life and that even our bodies abound with minute living and parasitic productions. This is a vulgar error and the notion is as disgusting as it is erroneous.” Clearly, the Committee for Scientific Inquiry wasn’t interested in an actual scientific inquiry.

Yet the independent investigations of Snow’s critics ultimately proved him right. Pastor and community organizer Henry Whitehead, initially as dismissive of Snow as everyone else, eventually identified the source of contamination of the Broad Street well—a cesspit located just three feet away. A mother that lived near the pump had washed her sick baby’s cloth diapers in water before dumping them into the cesspit. The baby later died of dehydration from severe diarrhea. When the cesspit was examined, the drain and brickwork was found in highly degraded state. There was no doubt what had happened—cholera had been transmitted to the well by seepage from the pit.

Despite a gradual vindication of Snow’s ideas, proponents of the miasma theory refused to go away quietly. Snow later came to the defense of ‘nuisance trades’ that produced noxious gases such as abbatoirs, tanneries, bone-boilers, soap manufacturer, tallow melters, and makers of chemical fertilizers. He explained his reasoning--that if the noxious odors produced by these manufacturers were “not injurious to those actually on the spot where the trades are carried on, it is impossible they should be to persons further removed from the spot.”

The medical journal The Lancet displayed nothing but contempt for Snow’s efforts, painting the manufacturers’ lobby as pro-miasma and accusing Snow of spreading misinformation: “The fact that the well whence Dr. Snow draws all sanitary truth is the main sewer.” Despite these attempts to silence him, many of Snow’s critics ultimately admitted that Snow was right a year later, providing greater support for the burgeoning sanitation revolution, which, even if originally aimed to rid the world of foul miasma, ultimately erased waterborne diseases such as cholera from modern life, and is rightfully regarded as the single most consequential development in the history of human health.

When I was younger, I always pictured William Farr as pompous and a man who let his arrogance blind him to the obviousness of what Snow was showing.

I recently read a biography of him [1] and came to realize my assumptions were completely misplaced. More amazing than discovering how Cholera was transmitted to, was that Farr realized he was wrong, admit it, and seek change based his error.

Yes, it took him 9 years of being wrong, and John Snow long since died, but that makes it more impressive how he was able to come to terms with his error.

I wonder if, rather than discussing his ideas in the London Statistical Society, he had been on Twitter and TWIV proclaiming Snow was wrong and it was clearly the elevation differences that cause Cholera, would it have been harder to admit error? Or would he have boxed himself in to an inescapable echo chamber?

[1] Victorian Social Medicine: The Ideas and Methods of William Farr

https://a.co/d/0B2TP0p

It's easy to take modern things, like toilets, for granted. It's stories like this that remind me how fortunate we are. Thanks for the perspective!